You might have heard the term “high jewelry” bandied about as you’ve gotten into the auction world. Or, in French, haute joaillerie.

What exactly is high jewelry, and how does it differ from any other fine jewelry? It’s not just a synonym for expensive jewelry, although it’s safe to say that high jewelry is likely to be very expensive.

When I sat down to write this post, I realized I don’t know what officially defines high jewelry either, and that’s with 35 years’ experience in the fine jewelry industry. I know what it is, of course, but to find a single definition that everyone agrees on? Not so much.

As it turns out, the definition of “high jewelry” is a little like pornography: you can’t really define it, but you know it when you see it. And thankfully it’s a lot easier to explain than pornography.

Nobody in the industry will deny that high jewelry should contain only the finest quality of rare gems and precious metal, be of distinctive design and exquisite craftsmanship (presumably handmade), probably comes from a famous designer or jewelry house, and so on. With all that, it’s obviously costly and it also holds its value. A very rare or bespoke piece is even quite likely to gain value, not just hold it.

How much value will it gain? Well, that depends on a lot, as we’ll see. And as if the already-subjective definition of high jewelry weren’t confusing enough, it also varies from U.S. to overseas, says jewelry historian Elizabeth Bonanno.

Are material, workmanship, and signature all that define high jewelry? Especially when many famous jewelry designers combine precious and non-precious materials and renowned international luxury jewelry houses also make pieces for ordinary people, not just rich or royal?

Tiffany & Co. still makes high jewelry pieces, but more of its revenue comes from mass-produced silver and gold pieces. Lovely, yes. High jewelry, no. Its website clearly differentiates its “high jewelry” from other pieces. Chopard’s website does the same, as does pretty much every single brand that offers both high jewelry and more affordable collections for the rest of us.

Cartier’s “Love” bracelet is a popular item and, as gold bangles go, expensive for its size and weight because of its provenance. It’s well made, clearly fine, and likely to fetch more in resale than a generic gold bangle because of the Cartier name—but it’s not high jewelry even if it is Cartier. Cartier’s diamond encrusted Panthère cuff, however? Definitely high jewelry! And those cats will hold their value even though Cartier has made a good number of them.

If you want to see a lot of high jewelry in one place, then the Place Vendôme in Paris is the best place to go. Originally laid out in 1702 as a monument to the successes of the army of King Louis XIV, the grandeur and exclusivity of the square (in the city’s tony First Arrondisement) attracted leading global luxury brands to set up shop there, especially jewelry, watches, and hotels. Many of the jewelry brands represented on the square are French and those are their flagship shops, but international brands are represented as well with their French outposts on the square. Some of the brands on the Place Vendôme or nearby Rue de la Paix include: Cartier, Chopard, Chaumet, Buccellati, Tiffany, Bvlgari, Boucheron, Bucherer, Breguet, Van Cleef & Arpels, Piaget, Patek Philippe, Vernet, Mauboussin, Jaeger-LeCoultre, and fashion brands Dior and Chanel, both of whom have high-jewelry collections.

And if you can somehow get an appointment (don’t count on it!) the number-one contemporary jewelry artist that global experts agree defines modern high jewelry is JAR. JAR (Joel Arthur Rosenthal) is an American-born artist who has lived and worked in Paris since the 1970s. He is to contemporary jewelry what Peter Carl Fabergé was to the latter 19th/early 20th century.

The notoriously reclusive jeweler not only routinely refuses to be interviewed, he doesn’t advertise, his shop has no display window, he only lets in a few very select clients, and he’s also been known to refuse to sell a piece—for any price—when he doesn’t think the buyer has enough artistic appreciation or taste to own it.

So if high jewelry is defined at least in part by the quality of its material, what about when a revered jewelry artist makes a piece that isn’t entirely precious? For instance, the American Daniel Brush is among those contemporary jewelry artists generally regarded by experts as someone whose work is collectible and likely to fetch very high premiums in resale. But Brush—goldsmith, sculptor, painter, jeweler—has been known to mix materials like pink diamonds and Bakelite, as he does in his famous “Bunny Bangle,” or even to use stainless steel or aluminum in his creations, which are considered art as much as they are jewelry. Nobody (at least nobody in their right mind) would start bargaining him down over it.

Nor is Brush alone in his willingness to use nontraditional jewelry materials. If there’s one defining characteristic of modern jewelry design—high or otherwise—the willingness to mix ultra-fine materials with mundane, quite ordinary materials would have to be it. Whether it’s then still considered “high jewelry” depends on the artist that made it.

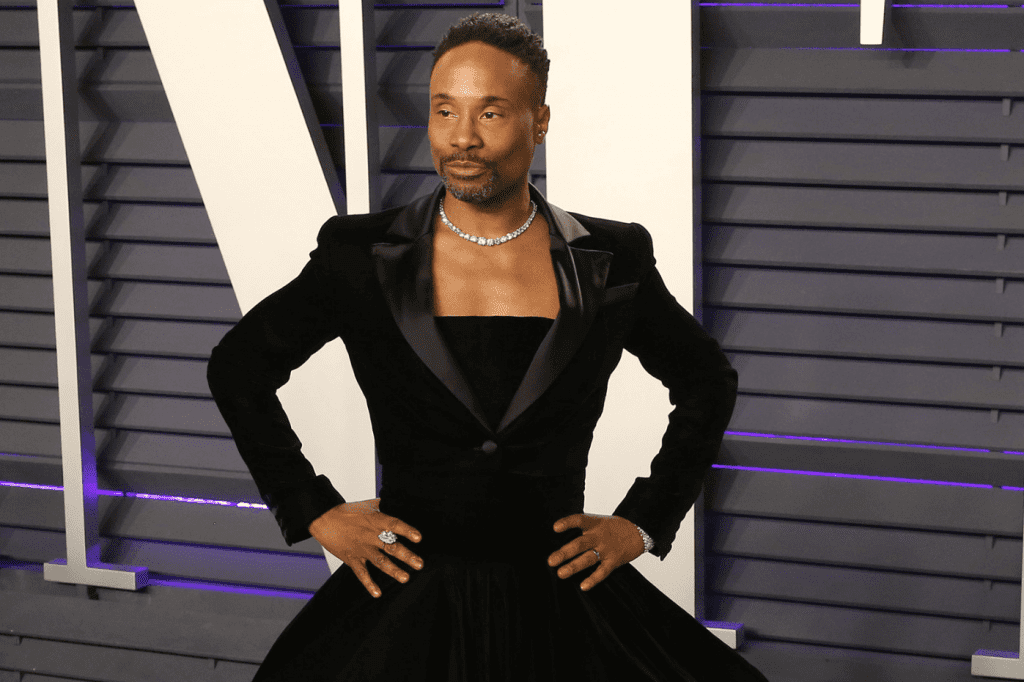

Along with JAR and Brush, Wallace Chan and Carnet’s Michelle Ong are universally put into the “high jewelry” category. Closer to home, Oscar Heyman — often called “the jeweler’s jeweler” for making high jewelry for other brands in their New York City atelier, along with their own collections—is another. Billy Porter is a huge fan and routinely decks out in OHB for his red-carpet appearances. We’ll look at these and other high jewelry brands in greater detail in upcoming posts.

As a final note, this discussion of “high jewelry” is in no way meant to downplay the value of high-end commercially available designers and brands. There are many, many names that fall into this category — Paul Morelli, Wendy Yue, Stephen Webster, to name just a few—whose work is currently available at fine jewelry and specialty stores, who also do high jewelry and bespoke pieces on request, and whose pieces are likely to hold their value for resale. We’ll look at some of those brands in upcoming posts as well.

Want to learn how to identify high end valuables hidden in your jewelry box? Click the banner below to read Worthy’s article now.

©2011-2025 Worthy, Inc. All rights reserved.

Worthy, Inc. operates from 25 West 45th St., 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10036