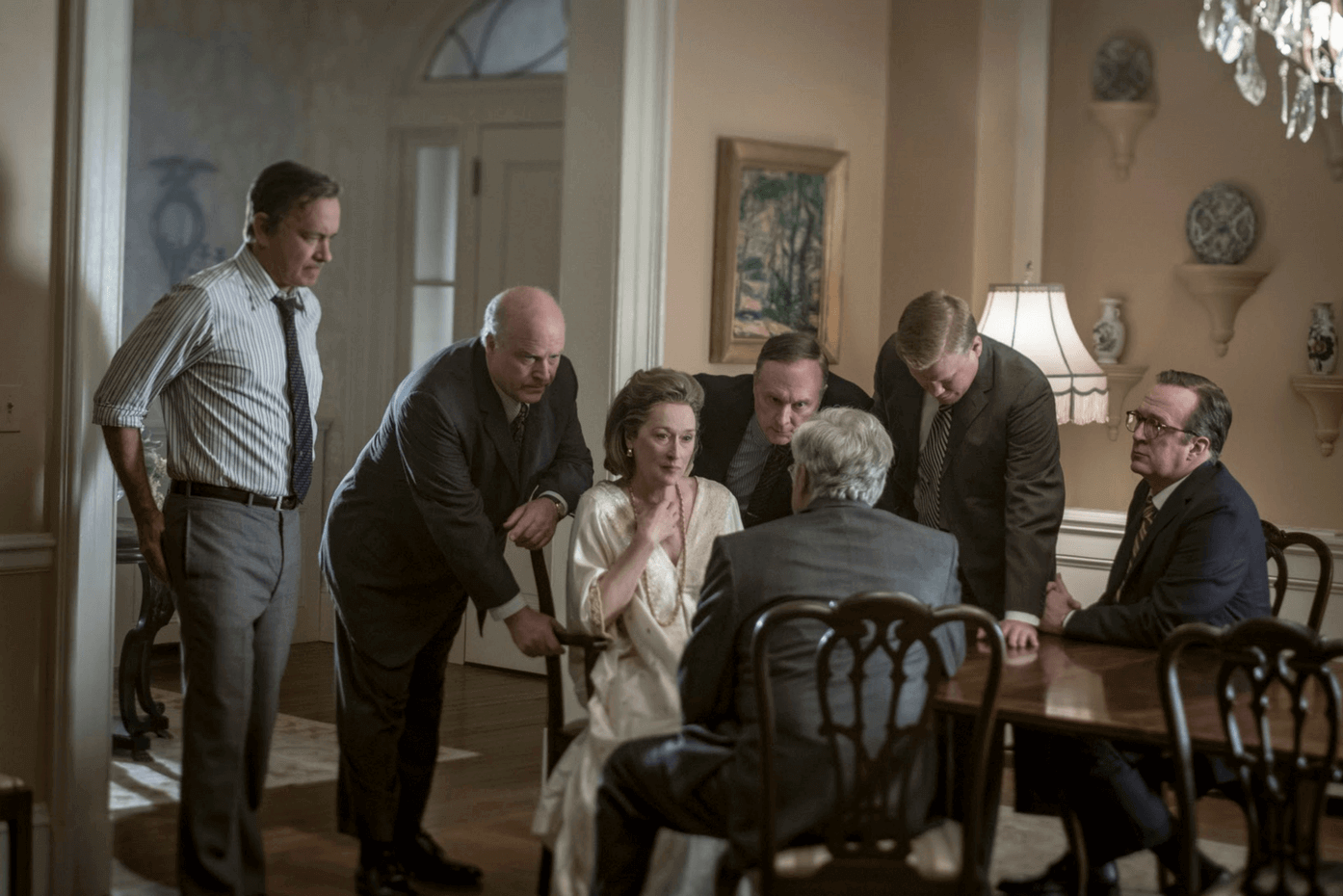

Photo credit: Niko Tavernise/Twentieth Century Fox

“Sometimes you don’t really decide, you just move forward and that is what I did – moved forward blindly and mindlessly into a new and unknown life…I essentially put one foot in front of the other, shut my eyes, and stepped off the ledge. The surprise was that I landed on my feet.”

These words of Katharine Graham, the first female CEO of a Fortune 500 company, describe the reality of a woman raised to be a society wife and mother, who in response to tragedy in 1963, takes over the family newspaper, The Washington Post.

In the newly released movie, “The Post,” we watch Graham struggle to find her voice. She knocks over a chair walking through a restaurant to meet with her editor, Ben Bradlee. Men walk in front of her and talk over her in the boardroom. And no one apologizes for expressing out loud their concern that she won’t have the resolve to make the tough choices.

Starring Meryl Streep as Graham and Tom Hanks as Bradlee, the film focuses on a time in the early 1970s when the First Amendment’s freedom of the press was tested in a battle with Nixon’s White House. When the New York Times received a temporary restraining order from continuing to publish a classified study on the Vietnam War, The Post must consider whether to print an exclusive from their own copy of what became known as the Pentagon Papers.

Facing possible contempt of court, devastating financial loss or even jail time, the question is significant and lands squarely on the shoulders of Graham. But she knows the paper will lose all credibility if they choose not to publish. Her positive decision reveals how she learned to stand up and speak out, while guiding her newspaper into its place in history.

Born into a wealthy family in 1917, married in 1940 and having four children, Graham was comfortable in her supporting role. She describes herself in her autobiography, Personal History as a rules follower, learning to get along wherever she might be. Only when looking back does she question why she never thought to create her own way.

When her father handed the reigns of The Post over to her husband, Phil Graham, she admits it never crossed her mind that it could have been her. Since her brother had gone into medicine, the family all saw her spouse as the only heir.

She loved her husband but characterizes their married life as one where he decided and she responded. Yet while willingly accepting her second class role, she believes it made her even more unsure of herself.

She was raised to believe a woman’s responsibility was to make her husband happy and had no training for how to be a successful executive.

In the late 1950s, Phil Graham began suffering from what was later diagnosed as manic-depression. Becoming even more immersed in his life and erratic mood swings, Katherine was his only support system as they decided to keep his illness private.

When he leaves her for a younger journalist, she is blindsided and suffers the humiliation of his public declaration to divorce and remarry. But his intention to buy out her shares of the newspaper is where she digs in, declaring that she’ll never give up the paper without a fight. He ultimately decided to return back to her, which she readily accepts, but not long after, he tragically commits suicide.

Appearing more comfortable hosting a dinner party than sitting in a boardroom, Graham is determined to hang on to The Post for her children. After her husband’s death, she recalls asking out loud what will happen to all of them. A friend pointed to her without saying a word. She knew then it was up to her.

Graham reveals in her autobiography that her initial struggles at running the paper were also influenced by the narrow way women’s roles were defined at the time. She was raised to believe a woman’s responsibility was to make her husband happy and had no training for how to be a successful executive.

Women of her generation often had a strong desire to please and Graham feels this made her almost incapable of making a decision that might cause someone to be unhappy. Even if she did issue a directive, she would add the phrase “if it’s alright with you.”

And there were few role models for her to emulate. Instead, there was an assumption that women were intellectually inferior to men, not capable of managing anything but their homes and children. Not only did she accept that but says the unfortunate result was that most of the women then became inferior.

Her life from daughter to wife to widow to woman parallels the history of women in this century, wrote Nora Ephron in her review of Graham’s autobiography. But although she was often the only woman in the room and feeling inadequate, she did become more self-assured in the determination to preserve her family’s legacy.

Beyond winning the right, along with the New York Times, to publish the Pentagon Papers in a 6-3 Supreme Court victory, The Post continued to successfully grow as Graham came into her own, attributing the women’s movement as helping her sort out her thinking. She came to see, in her words, that women weren’t put on earth to catch a man, hold him and please him and began asserting herself.

Working tirelessly to learn the business, she gained the confidence to contribute ideas, criticism or praise of stories that appeared in The Post. She even passed along a scoop to Bradlee that Jackie Kennedy was going to marry Aristotle Onassis – but he chose not to publish because he was skeptical.

Crediting Gloria Steinem with changing her mind-set, they became friends and Graham provided $20,000 for seed money to help start Ms. Magazine.

The Post’s investigation into the Watergate case led to the paper winning a Pulitzer Prize.

Graham received a Pulitzer Prize for her autobiography, “Personal History” and was also awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

When she took over The Post, she felt inferior to the men who worked for her. Her reciting of a quote by essayist Samuel Johnson as he characterized a woman’s preaching, revealed how she felt in the male-dominated publishing world. Described as similar to a dog walking on his hind legs, Johnson had said “it is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.”

READ ALSO: Is Reese Witherspoon Able to Take Us ‘Home Again’?

At the theater where I saw the film, everyone applauded in the end. I’m sure it was in response to the subject matter and the ultimate victory of the American people. But I think many were also celebrating the woman who carried so much on her shoulders but finally, and gracefully, found her footing and her voice.

©2011-2025 Worthy, Inc. All rights reserved.

Worthy, Inc. operates from 25 West 45th St., 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10036