If you are someone who inherited a round-brilliant diamond cut between 1860 and 1920, then tried to sell it in the 20th century, you were likely told the stone was an “old European cut.” You were also likely told that it needed to be re-cut to modern proportions. Then you were offered a heavily discounted price that factored in whittling it down to bring it up to current standards.

That’s what happened to me when I tried to help my newly-divorced sister sell her heirloom diamond ring around 1970, in the heyday of prejudice toward old-style cutting.

Actually, I should say “almost happened.” Although it was two years before I became a jewelry journalist, some instinct told me to distrust every one of the five jewelers I showed the stone to who dismissed it as, to quote one of them, “a dinosaur.” Finally, a sixth jeweler on Philadelphia’s famous Jeweler’s Row looked at the stone and said it was a magnificent specimen of “old-style cutting.” As such, he said, it was worth nearly as much as he would pay for a contemporary-crafted stone. Accordingly, he offered to pay a far larger sum than any other offer we had received–but only after begging my sister to keep it for her children. “You don’t see diamonds like this anymore,” the jeweler lamented, “and I think it’s a shame.”

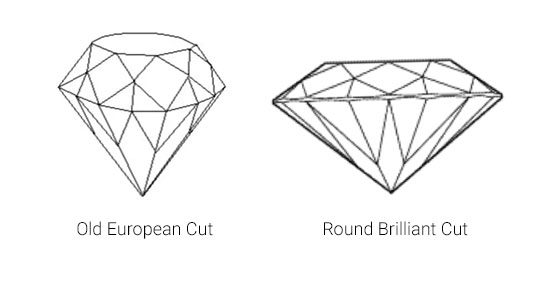

It wasn’t until 2000, when I began a two-year stint working for a cutter of “hearts and arrows” diamonds, that I realized what the jeweler was talking about. It was then that I learned that “Old European Cuts” were nothing of the kind. Extensive historical research conducted by gemologist Michael Cowing and GIA’s Al Gilbertson showed that round diamonds with small tables, high crowns, and large reflections from broad pavilion main facets were really not old or European at all. They were, in fact, American, first fashioned around 1860 by Boston cutter Henry Morse whose shop foreman, Charles Field, had invented and patented the first girdling machine. This technology enabled Morse, whom many consider the true father of the “ideal cut,” to fashion perfectly circular diamonds for the first time in history. “If anything,” Cowing quips, “the cut should have been called the new American round brilliant.” Why wasn’t it? I asked.

Blame Marcel Tolkowsky. Tolkowsky, as you may know, was the inventor of what has evolved to be known as both the “American ideal cut” and the “Tolkowsky ideal cut”. He was the first well-known exponent of cutting diamonds for beauty instead of weight. In his famous treatise on ideal (actually, he called it, more modestly, “best”) diamond cutting, self-published in 1919, the Belgian cutter cited the claims of American journalists that Morse had already created a similar cut. Over the years, the rounded brilliant shape with ideal angles first cut by Morse was adopted by cutters in Antwerp and Amsterdam. As this design became standard in Europe, it became known as a kind of vintage round-brilliant, or, as gemologists were taught for years, the “Old European Cut.”

Cowing thinks this phrase is as dismissive as it is inaccurate. “For decades, ideal-cut zealots wanted the jewelry world, and the public it serves, to think of the Morse round-brilliant as a kind of outmoded precursor to the modern ideal cut,” Cowing explains. “While it may have been transitional, it was a cut with distinct virtues that most modern round-brilliants lack.”

Old European Cuts are staging a comeback as high-flair vintage diamonds and objects of true beauty in their own right.

And here is where I beg any reader in possession of an Old European Cut diamond to look at it with new eyes. You will not be alone. Suddenly, after years of neglect and ridicule, Old European Cuts are staging a comeback as high-flair vintage diamonds and objects of true beauty in their own right. As a result, the once-wide price differences between old and modern brilliant cuts are shrinking rapidly. “It is no longer ‘mandatory’ to recut them–unless, of course, they’re poorly crafted,” Cowing notes. “Old European Cuts are now enjoying a revival in popularity as ‘Vintage Ideals’.”

What’s the “Old European Cut” cut got that makes it so newly, fashionably attractive?

In a word: fire.

I’m talking about spectral fire so vivid that in “fire friendly” lighting these diamonds give the finest opals a run for their money. “Fire,” the attribute gemologists call dispersion, is a nearly extinct esthetic attribute for diamonds today. A century ago, it was as commonly perceived and prized by purchasers as brilliance. Where did fire go? Or, more accurately, who put it out?

No one would be more grieved to see the disappearance of diamond fire than Sir Isaac Newton, the father of gravity. He expressly singled out diamond for its exemplary dispersion of spectral colors in his 1704 treatise, “Optiks.” Indeed, his respect for what he called the gem’s “refraction” was so great he is said to have named his pet pomeranian, Diamond.

Newton was far from alone in his reverence for diamond fire. I like to imagine him walking into a London jewelry store two centuries later and being shown an Old European Cut. He would have seen stones that breathed fire as much as they burst with brilliance. In pre-electric, gas-lit stores, flickering illumination was conducive to producing broad flashes of dispersion. So diamonds weren’t only known for their reflective powers, as they are today, but also their spectral dispersion powers. When jewelry store customers examined diamonds for purchase, their attention was called to both the diamond’s brilliance (reflected white light) and its fire (rainbow colors of spectral dispersion). Although diamond advertisements still extol diamonds for their fire, the truth is that only a handful of diamonds possess this wonderful trait to the degree common a century ago.

What has happened is that newer cutting designed to increase the diamond’s sparkle (known as “scintillation”) does so at the expense of fire. Once you see real diamond fire, you’re not likely to forget it.

Unsurprisingly, many who see fire for the first time won’t tolerate its absence in any other diamond. “A diamond with little or no fire is half a diamond,” says Martha Hoefer, whose husband, Tampa appraiser Bill Hoefer bought her a 3-carat “Old European Cut” diamond a decade ago as an anniversary present. Martha says she felt like Prometheus stealing fire from the gods when she first looked at it. “I was on an airplane and the light coming into the cabin and hitting the diamond made giant rainbow reflections on the walls and ceiling,” she remembers. “I put on a light show for my fellow passengers. One of them told me, ‘My diamond doesn’t do that’.”

Few modern-cut diamonds “do that”–namely, put on fireworks displays. One of the reasons I have long been a tireless proponent of hearts-and-arrows diamonds is that they are cut to such exacting proportions and precision that they flash with fire as much as they burn with brilliance. I remember sitting with Richard von Sternberg, EightStar’s president, in a trellised wine garden, with coruscating sunlight shining through the slats, and seeing the 1-carat K-colored EightStar diamond he wore on his finger erupt with colors like a 4th of July sky. It was one of the most magical moments of my 40-year career in the jewelry industry.

Martha Hoefer experienced the same ecstasy with her 3-carat Old European Cut. What’s more, the high brilliance of her stone masked the yellow tinge responsible for its GIA color grade of K. “You put my Old European Cut K-color next to a typical modern-cut K-color and my stone looks whiter,” she exclaims. This is no hollow boast. I did the same K-color comparison of Richard’s hearts-and-arrows stone with conventionally cut ones numerous times and realized ideal cuts are much kinder to cape stones than typical diamonds.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not advocating a return to vintage cutting styles. I’m just asking due respect be given them–and proper lessons learned.

What makes Old European Cuts play so many tricks with light?

When a modern round-brilliant is cut to the right proportions, it displays two kinds of light discharge–brilliance and fire–in maximal quantities. I call these stones “high-performance diamonds.” Perhaps I should call these fire-breathing ideal cuts: “high-ignition diamonds.” Diamonds that combust with both searing brilliance and prismatic fire are an apt symbol of love’s fire and an everyday reminder of a couple’s passion and intensity.

But why do so many vintage diamonds catch fire? Cowing says it’s their ample crowns and broad pavilion main facets. As ignition-ready stones, they exploded like tinder when struck by “fire friendly” light. What’s more, diamonds didn’t have to be round to be set ablaze by light. If cut symmetrically with similar broad main facets, cushions and squares are just as prone to catch fire. Indeed, this is why many cutters are experimenting with custom cushion and rectangular cuts that outshine conventional diamonds in both brilliance and fire.

While on the subject of fiery cushion cuts, it would be good to deal with another kind of vintage style, the “Old Mine Cut,” that is often confused with the “Old European Cut.” The term “Old Mine” is a broad one that refers to cushion-shaped brilliants that were the precursor of the round-brilliant. Before the advent of modern girdling machines, the brilliant cut was cushion shaped closer to its natural square crystal outline. If the jewelry trade wants to recognize and abide by the corrected history of diamond cutting which establishes the round “Old European Cut” as the round brilliant cut of the late-19th century, it would be equally correct to revise the meaning of the cushion-shaped “Old Mine” to refer to a “pre-modern brilliant cut.” In other words, it would be correct to call “Old Mine Cuts” what they really are: cushion shaped “Old European Cuts” as cut in Europe prior to the round brilliant. Such revision of terminology and thinking could mark the beginning of a revival of retro and vintage cuts as a grateful buying public warms to what it’s been missing in diamond beauty for far too long.

©2011-2025 Worthy, Inc. All rights reserved.

Worthy, Inc. operates from 25 West 45th St., 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10036