Did you ever come home from school with a D on your report card?

I did, and it wasn’t a fun experience. I had always done well in school, but once I hit sixth grade and math class evolved from basic arithmetic to beginning actual mathematics, my straight-A streak ended with a bang. I got my first C in sixth grade, and my first D in seventh. No matter how much my teachers or my parents tried to explain the concepts, it just didn’t connect.

I struggled through algebra, analytical calculus, and chemistry, but aced geometry and physics. (It would be four decades and one Apple Store genius later that I understood why. I’m a visual learner, and I aced geometry and physics because I could see the calculations in a demonstration. The genius who put an iPad in my hands had me at “are you a visual learner?”)

So while we don’t want a D on our report cards, every diamond would love to get a D! It’s the very best color a diamond can be.

Why is that?

Gemological Institute of America (GIA) introduced its diamond color grading scale in 1953. Now the industry standard, the scale for colorless diamonds begins with D and progresses to Z.

It is not, as commonly believed, to leave room in case new diamonds discovered in the future are better than D. It’s because the original ways jewelers described diamonds were all over the place. People would use comparison terms like “river,” or “water,” numeric values, or letters like “A” or “AA” or even “AAAA.” And there was no industry-wide agreement as to what even constituted one A, let alone four.

In the depths of the Great Depression (a time when people were selling off a lot of jewelry), a former retail jeweler named Robert M. Shipley saw the need to institute a uniform set of standards for the jewelry industry. He founded GIA in 1931 as an education and research facility dedicated to the study of gems, and to this day is revered as the man responsible for revolutionizing the jewelry industry. He coined the concept of the Four C’s, and in addition to GIA, Shipley also founded the American Gem Society in 1934 as a professional guild of knowledgeable and trustworthy jewelers.

Since its early days under Shipley, GIA was working to develop an accurate, objective color-grading system for colorless to light yellow diamonds. The goal was to develop a system based on absolutes, instead of relative terms and vague descriptions. A new way to describe color evaluations was needed, and letter grading made the most sense. But it had to be done in a way that wasn’t going to be confused with the existing hodgepodge of letters.

Nobody was using D for a grade because, like in school, it had a negative connotation. Shipley’s protégé and successor Richard T. Liddicoat—himself a gemological legend—chose D as the place to start because it was unlikely to be misinterpreted or misused. Each letter from D to Z represents a range of color based on a diamond’s tone and saturation, and GIA’s color scale became the global industry standard used today.

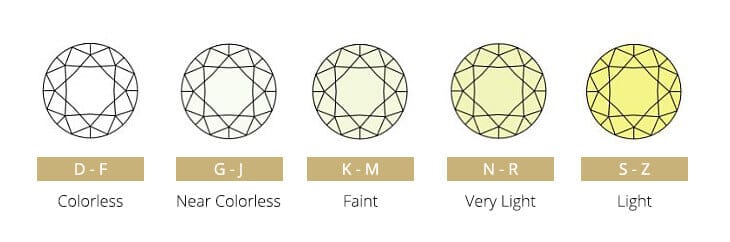

D means the diamond is fully colorless. E and F are also considered colorless on the GIA scale, at least insofar as the naked eye can see. A high-power microscope can reveal minute differences between D, E, and F, but the naked eye can’t see it. The higher the diamond is on the color scale, the more valuable it is, and there’s an even bigger jump in value for the three colorless grades and especially D.

Colorless (colloquially called “white”) diamond grades progress from D down to Z. But that’s not where the story ends. A diamond whose color is more saturated than Z is re-classified as a fancy color diamond, and its value then begins to climb again: more color equals more value. More on that shortly.

In addition to establishing a color scale, Liddicoat and his colleagues also devised a methodology to grade a diamond’s color accurately and consistently, including the exact wavelength of light to be used, a precise way to hold and view the diamond, and the background color against which this all takes place. He also pioneered the development of master stone sets: diamonds of predetermined color against which every other diamond is carefully compared. This is to ensure that every diamond is graded with the same standards and in an identical environment.

While an experienced jeweler with a GIA Graduate Gemologist (G.G.) or AGS Certified Gemologist (C.G.) designation can grade a diamond quite accurately in the store, it’s standard procedure for stones above a certain value to have a third-party verification (i.e., grading report) from GIA, AGS, or another reputable gem lab.

Visit a professional lab, and the first thing you’ll notice is that the grading room is dark. Even a little ambient light in the room can impact the appearance of the stone as the grader views it.

Each diamond grader has a special light box at his or her workstation. The inside color, a neutral white, and the light source are both calibrated to Liddicoat’s standards. The grader positions the diamond as Liddicoat devised, views it through a microscope, and compares it to the master set of stones to determine its color grade. In addition to color, it’s also being graded for its clarity, the quality of its facet arrangement (cut), and getting weighed (carats).

So, we’ve discussed that the most valuable color grades are D, E, and F. Diamonds with grades of G, H, I, and J are considered “near colorless,” but the naked eye usually cannot discern the color, especially at G and the better H ranges. Combined with a good cut and clarity, these stones are still highly valuable and costly compared to comparable stones with lower color grades. As grades go lower into the J range down through K, L, and M and below, the stones are considered “commercial” grades, and the price drops accordingly. These are the stones you’d typically find in jewelry sold at mass market stores or that’s advertised at a “discount.”

Now, that’s not to say these are bad stones. They’re not. They’re still considered to be gem quality, and there’s a lot that can be done to visibly enhance their appearance. An excellent cut that produces tremendous scintillation and sparkle will dramatically improve their color appearance to the naked eye. The setting they’re put into also can enhance (or detract from) their color appearance. Using them as accent stones next to a colored gemstone makes their own color appearance less visibly important. And, finally, a very small percentage of diamonds also possess a quality called fluorescence that can impact the appearance of their color.

Fluorescence is a natural property that makes a diamond glow blue under ultraviolet light (such as in a nightclub) but more importantly also helps it to appear more radiant in ordinary sunshine. It comes from trace elements such as nitrogen, hydrogen, or nickel caught within the stone during the carbon crystallization process. Certain rare combinations of those elements will produce fluorescence.

A medium to strong degree of fluorescence can help a stone with a lower color grade appear better to the naked eye, but it’s essential to understand that fluorescence doesn’t impact a stone’s 4C grade. It’s noted on the grading report as a characteristic of the stone, but it does not increase or decrease its value.

Not surprisingly, there’s a scale ranking of fluorescence ranging from none to very strong. About one-fourth of all diamonds possess some degree of fluorescence, but only those with strong enough levels—fewer than 10% of all stones—will exhibit the UV-glow phenomenon.

So between cut, setting, and possible fluorescence, a diamond with a color grade in the “commercial” range can be made to visibly appear much whiter than its actual color grade suggests, which results in significant cost savings for the buyer.

A diamond with color more saturated than Z begins to regain value again as a fancy color diamond and will be graded by a completely different set of standards. Most of the parameters used to evaluate colorless/white diamonds will no longer apply.

With a fancy color diamond, color is the first and foremost determinant of its value, so it will be cut to present the best color appearance when face up—and those facet arrangements might be radically different than would be used for a colorless diamond. Even its size will take a back seat to color. Of course, a bigger fancy color stone is going to be more valuable than a comparable small one, but it is not unusual for a skilled cutter to re-cut a large, light stone to try and bring out more color—even if it means losing some carat weight. Recently, New York-based colored diamond dealer Larry West of LJ West was featured on CNBC doing just that to a large pink diamond. By shaving a few points off some of the facets, he successfully doubled the value of the stone from $3.2 million to over $6 million.

Fancy color diamonds are graded by both the intensity and hue of their color. Intensity ranges from light (most affordable) to fancy to intense to vivid (most costly), with varying degrees of each. On GIA’s colored diamond reports, grades in order of increasing color strength are: Faint, Very Light, Light, Fancy Light, Fancy, Fancy Intense, Fancy Vivid, Fancy Dark, and Fancy Deep. The stone is also evaluated for modifying colors: is it pink or purplish pink? Sky blue or grayish blue? A modifying color might—or might not—lower the value of a stone. Grading fancy color diamonds is a more subjective process than white diamonds, because the beauty of color is in the eye of the beholder.

©2011-2025 Worthy, Inc. All rights reserved.

Worthy, Inc. operates from 25 West 45th St., 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10036